Bic’s disposable underwear: a lesson in market adaptation

When we hear the name Bic, a disposable pen usually comes to mind. However, Bic has also been well-recognized for its disposable lighters and razors. One lesser-known chapter in Bic’s history involves an ambitious yet unsuccessful brand extension: disposable underwear.

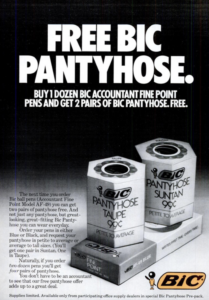

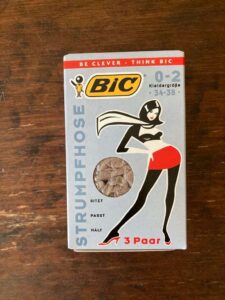

In the late 1970s, the company decided to venture into the market for disposable pantyhose. The concept was straightforward: offer pantyhose that were “high quality, low price, and disposable,” mirroring the principles behind their successful pens. These pantyhose were primarily targeted at office managers and secretaries, aiming to integrate them seamlessly into office supply purchases.

Despite the strategic alignment with their disposable product line, the pantyhose failed to gain significant traction. Sales were sluggish, but Bic continued to sell them for several years, with some units even available as late as 2024, such as in Austria.

There are also rumors that Bic launched disposable underwear. While an image purportedly showing a woman wearing Bic disposable underwear circulates on the internet, it is likely a fabrication. There is little evidence to support the actual existence of such a product.

Nevertheless, the foray into disposable pantyhose stands as a cautionary tale in brand extension. While the idea seemed aligned with Bic’s core competency in disposable products, it ultimately did not resonate with consumers. This example underscores the importance of market research and consumer demand when considering brand diversification.